Legal experts say risks to the plastics industry are not lessened by the collapse of the global plastics treaty negotiations

The legal risks faced by businesses in the global plastics supply chain are increasing, despite the breakdown of talks to agree a global plastics treaty in August, suggest legal experts.

Every day, the equivalent of 2,000 rubbish trucks full of plastic is dumped into the world’s oceans, rivers and lakes. ClientEarth senior lawyer Kamila Drzewicka tells Sustainable Views that plastics carry “transition, reputational, physical and liability risks” due to their impacts on the environment and human health.

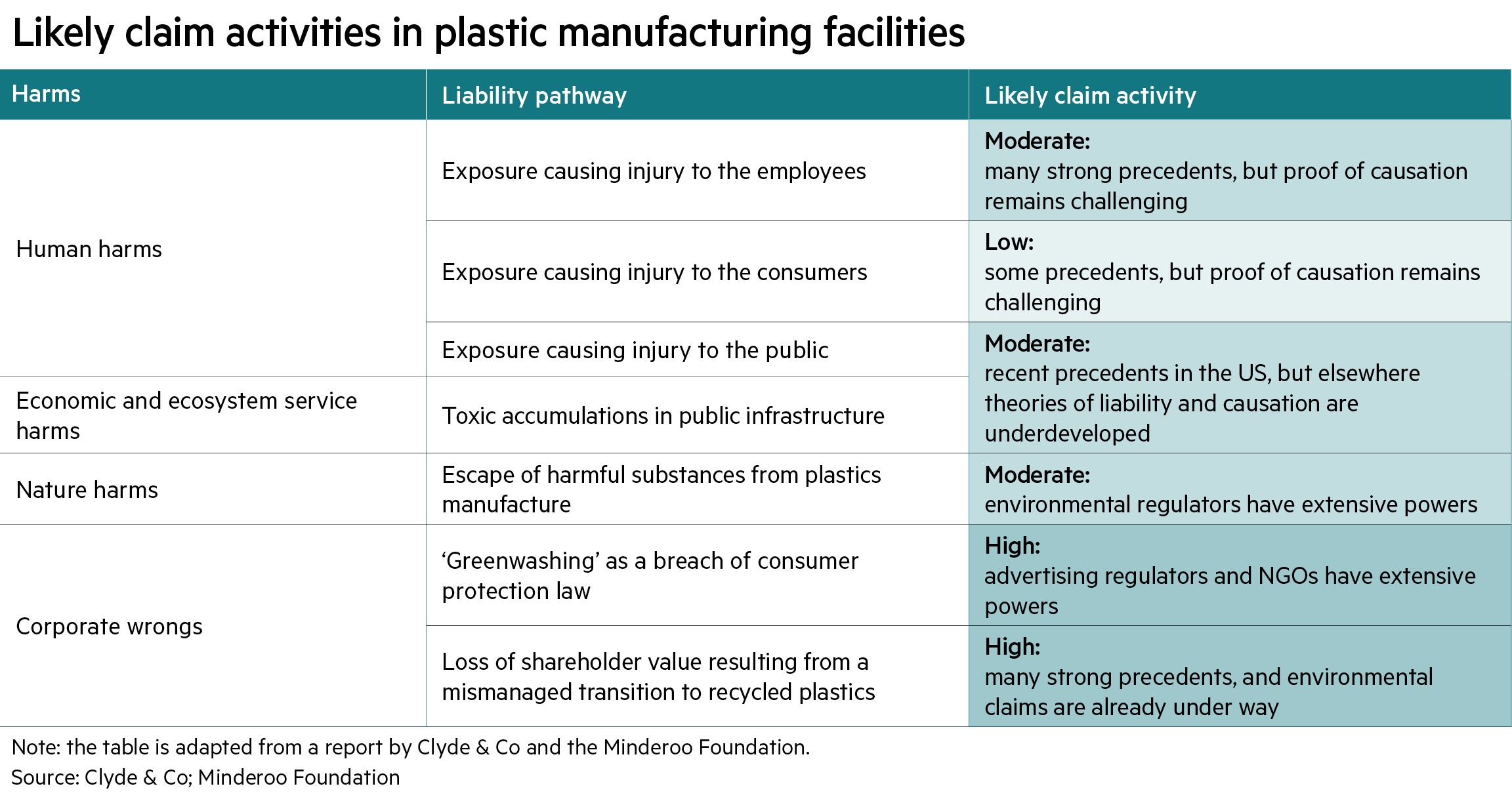

Greenwashing lawsuits remain the most common legal challenge levelled at the plastics industry, Neil Beresford partner and environmental liability specialist at international law firm Clyde & Co, tells Sustainable Views.

London-based ClientEarth filed a lawsuit against Nestlé Poland on September 18, accusing the company of including misleading recycling claims on its Nałęczowianka bottled water.

The legal non-profit says that slogans used by the brand on its packaging — such as “I am 100 per cent made of recycled PET plastic (not applicable to the cap and the label)”, “I am made from another bottle”, and “I am recyclable” — create a “false impression” that single-use plastics are not harmful to the environment.

A survey commissioned by ClientEarth in 2024 found that 80 per cent of respondents in Poland and Germany believe products with recycling logos will be recycled if properly disposed of. This assumption is, however, flawed as recyclability is determined by local infrastructure, with around only half of plastic bottles in the EU being recycled and roughly 30 per cent of them used to make new bottles, says the non-profit.

Whether plastics can ever be truly circular is debatable as they degrade over time and most cannot be recycled more than a couple of times. Often, virgin plastic is blended with recycled plastic to make new products. ClientEarth argues that statements which suggest plastics are “circular” or “sustainable” are misleading.

The Coca-Cola case

This is not the first time Nestlé has been under fire for its recycling claims. In 2023, EU consumer protection organisation Beuc, supported by ClientEarth and another non-profit the Environmental Coalition on Standards, filed a legal complaint against Coca-Cola, Nestlé and Danone with the European Commission over their “100 per cent recycled” and “100 per cent recyclable” claims on plastic bottles.

Coca-Cola agreed to adopt new labelling to make it clear which parts of its bottles are made from recycled plastic.

Nestlé and Danone are yet to reach an agreement with the commission. Danone and Coca-Cola declined to comment, while a spokesperson from Nestlé’s water division tells Sustainable Views that its conversations with the commission “continue”.

Greenwashing risk here to stay

Beresford says plastics companies should expect more greenwashing lawsuits and describes recycling claims as particularly “dangerous territory”.

In addition to the risk of litigation, greenwashing also presents a regulatory risk in some jurisdictions.

In the EU, the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation limits the use of misleading sustainability claims. The PPWR has been in force since February across all 27 EU member states, but the commission has until January 2028 to adopt delegated acts on recycling criteria.

The EU’s Green Claims Directive, if it ever sees the light of day, would also work alongside the Directive on Empowering Consumers for the Green Transition to protect EU consumers from misleading sustainability claims.

Regulators in the UK have also been actively pursuing greenwashing. The Competition and Markets Authority was granted powers to issue fines under the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act, which came into force in April, and can target companies misleading consumers, including with green claims.

Regulatory risk is lower in the US, but litigation risk remains high owing to the country’s “lively” litigation culture, says Beresford

Litigation grows independently of regulation

While an agreement to establish a legally binding plastics treaty would have prompted jurisdictions to adopt the regulation, litigation against companies in the plastics supply chain can continue without a treaty or regulation, says Beresford.

Individual consumers or employees of plastics manufacturers can bring forward claims, for example, that exposure to plastics has damaged their health.

Gathering sufficient evidence that an individual producer or plastic company is responsible for health impacts can be challenging for claimants, but can be is easier for an employee exposed to a high level of a specific plastic, adds Beresford.

Scientific understanding of the effects of microplastics on human health is still evolving, but early studies suggest they could be linked to cancer and reproductive issues.

Countries that receive large shipments of plastic waste could also bring forward pollution litigation, says Beresford. This is especially a risk for companies if their packaging is easily identifiable or branded as the responsibility can be traced back to them.

Businesses across the supply chain could be exposed to these risks, including manufacturers, consumer goods companies and marketing firms, he adds.

International courts raise the bar

International courts are also setting a precedent for states and companies to protect citizens against climate harm, Beresford says.

In July, the International Court of Justice delivered a legal opinion making it clear that states and companies have a “legal duty” to mitigate against climate change under international law.

Prior to the ICJ opinion, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, based in Costa Rica, also issued an advisory opinion stating that people have a human right to a healthy climate and states have a duty to protect that right.

While these cases relate to climate change and emissions, rather than plastic pollution, they establish a “basic rule book” of corporate liability for environmental harm under international law and could be used to inform future cases, says Beresford.

Reuse and refill remains minimal

Refillable and reusable packaging would help large consumer goods companies to reduce their use of plastics and therefore their risk, Drzewicka says. But brands are not adopting these strategies beyond small pilot projects because “virgin plastics are still cheaper”, she argues.

Indeed, large companies have been scaling back their ambition when it comes to plastic reduction targets.

Unilever pledged in 2019 to cut its virgin plastics use by 50 per cent by 2025. In 2024, it said it was aiming for a 30 per cent reduction by 2026 and a 40 per cent decrease by 2028, and continues to sell many of its products in unrecyclable plastic sachets.

A Unilever spokesperson said “transformation takes time” but that the company is “working towards a future where plastic is reduced, and packaging is reused, recycled or composted”.

Similarly, Colgate-Palmolive said in its 2023 sustainability report that it may miss its 2025 goal to make all of its packaging recyclable, reusable or compostable.

Nestlé tells Sustainable Views that as of 2024 it had reduced its plastics use by 21 per cent compared with a 2018 baseline year, and is seeking to increase this to 33 per cent by 2025.

Danone, updated its vigilance plan this year to account for plastics risk following engagement with non-profits.

However, Drzewicka argues that companies are still overly reliant on recycling as a solution. To truly mitigate the risks associated with plastics, companies must develop “new ways to distribute their products”, she says.